(originally printed in the design issue of 61° North Magazine)

Kodiak Island is hard on buildings. Wood rots. Metal rusts. Rain finds the leaks. Freight is expensive. People here reuse for economy and practicality, like the shipping containers repurposed as storage sheds and offices around town. Sometimes the act of adapting what’s available leads to interesting spaces and design.

Kodiak Island is hard on buildings. Wood rots. Metal rusts. Rain finds the leaks. Freight is expensive. People here reuse for economy and practicality, like the shipping containers repurposed as storage sheds and offices around town. Sometimes the act of adapting what’s available leads to interesting spaces and design.

For the few months it was open in 2014, everyone was talking about the repurposed Bering Sea crabber being used as a floating bar and strip club in the channel.

Over time, Kodiak’s rainforest swallows structures. The moss and trees growing over old WWII bunkers around town only added to their appeal when we were kids daring each other to run through the cool, dark spaces.

~

At the base of Old Women’s Mountain, a row of nine fuel bunkers seemed to be fading into the hillside, most people didn’t even notice them driving by. Janet and Bob Johnson purchased one from Lash Corporation about ten years ago, on an acre and a half of industrial property. It came with a waterfall. They’re currently the only residents in their unusual neighborhood, but several others are under construction. Now it’s easy to spot the Johnson’s building from the road. They’ve sided it in green and topped it with a custom-made finial with three metallic balls like an enormous Christmas ornament.

Renovating the bunker wasn’t simple, or cheap. The concrete walls are 12 inches thick and reinforced with rebar. “It took two guys a full day just to cut out one window,” Janet says. They only cut two, but the third floor addition has 6 floor-to-ceiling arched windows and brings the total space to 3,000 square feet. A large goat head sits on the kitchen table, where Janet has been puzzling out how to turn it into a hat for a client. She runs her taxidermy business from the garage. The kitchen and a single bedroom and bath make up the caretaker’s apartment on the second floor. It’s the top floor that makes the place.

This room showcases the octagonal interior, the ocean just fifty yards away, and expansive views of Women’s Bay and the mountains around it. On stormy days, helicopters hover over the bay during Coast Guard rescue drills.

This floor used to be office space, before the Johnsons sold their plumbing company.

“I kept saying, one day this is going to be the most fantastic living room,” Janet said.

Enormous plants thrive in the sunny windows, including a fig tree that Bob points out because it took him two years to get the seed to grow and came from a Florida cab driver eating figs while he drove Bob around fifteen years ago. Cased beams to fortify the building against strong winds display taxidermy mounts from hunting trips around the world and a collection of walrus art (the mascot of their plumbing company).

This is where the Johnsons entertain and relax, with their cat, a pit bull, and two Rottweilers that wrestle between mounted animals—a wolverine, a New Zealand possum, a turkey—and furniture draped with furs. A mirrored bar made in South Africa fills the back of the room. It’s so large they needed a boom truck to lift it into the bunker. The story goes that it’s made of ironwood from an African railway line plagued by killer lions, according to the book, The Man-Eaters of Tsavo, displayed on the counter.

It’s hard to imagine this was once a windowless concrete storage shed.

“It’s probably the most unique house in all of Kodiak. I mean, it’s a WWII bunker,” Janet said, “There are beautiful, beautiful homes here, but this one is not only unique, it’s historical.”

~

The Star of Kodiak is another WWII relic that most locals think of as just another seafood processor in a waterfront crowded with canneries.

It’s the only remaining ship brought as an emergency shrimp and crab processor in the wake of the 1964 tsunami, when a 30-foot wave destroyed Kodiak’s canneries in the midst of a phenomenal king crab boom. In the rush to restart the industry, people looked for anything that floated and could be refitted into a processing plant.

The Star of Kodiak is also one of the very last of 2,700 WWII Liberty ships built between 1941 and 1945. Some were lost during the war to torpedoes, kamikazes, and mines, several broke in half because the steel turned brittle in cold ocean waters, but most were scrapped in the decades following WWII. There are only two operational Liberty ships left. The Star was once the Albert M. Boe—part of a fleet of mass produced cargo ships that revolutionized ship building. The vessels could be made in 40 days or less, by using prefabricated, standardized parts and welding innovations. About 592,000 man hours went into this ship. Man and woman hours—women made up almost half of the shipbuilding workforce. The goal was “to build ships faster than the enemy could sink them.” Of the two hundred Liberty ships in the D-Day armada, several were deliberately sunk off Normandy beachheads to create a manmade harbor. These ships were slow at an av erage 11 knots. But they could carry the load of 300 railroad boxcars, or 440 tanks, 2,840 Jeeps, or 230 million rounds of rifle ammunition. Their propellers alone weighed 21,000 pounds. Troops traveling to the front on Liberty ships slept in bunks stacked five tiers high. Today, Trident Seafood’s logo is painted on the stack. Even infilled and missing its 18-foot propeller, even with holes cut in the side for forklifts and a warehouse addition, the 441-foot-long Star of Kodiak still looks enough like a ship ran aground that Kodiak visitors mistakenly believe it was washed into place during the tsunami. Staterooms on the top deck have been empty since a 1997 fire, the narrow hallways lit only by portholes. Over time the three floors inside have been refitted with a maze of processing equipment to handle dozens of species: crab, scallops, halibut, rock fish, sole, cod, and salmon. These gleaming processing belts contrast with the ship’s outer decks, exposed to the elements and used mainly for storing fish totes and ammonia tanks.

In spite of an annual paint bill of approximately $25,000, the Star of Kodiak shows her age in places. “There’s not enough paint in the world,” says plant manager, Paul Lumsden.

Still, the Star of Kodiak endures, while the half dozen other ships hauled north as processors in 1964 are gone.

~

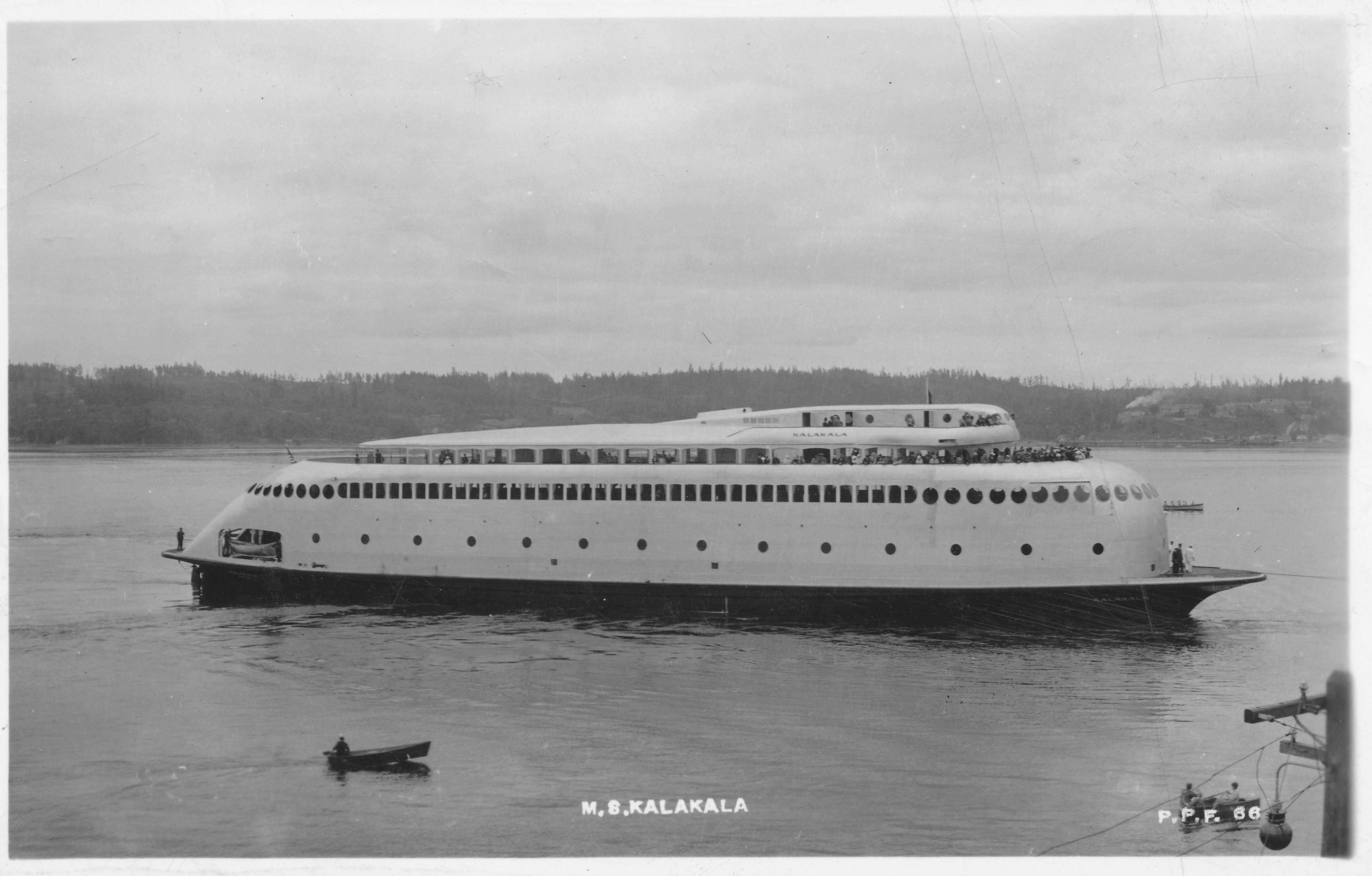

The most famous of these processor ships, the Kalakala, would eventually be reclaimed from Kodiak because of her iconic form. The Art Deco design resembled a giant airstream trailer, and this rounded motif was used throughout the ferry’s interior. The Kalakala was alternately referred to as the flying bird, the floating toaster, or the silver slug.

For a time, the Kalakala was Puget Sound’s best-known ferry—the symbol of Seattle and most popular attraction at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair after the Space Needle. Her futuristic design was intended to boost morale during the depressed 1930s; for $1.00 people could take

“Moonlight Cruises” with live music and dancing on board. She even had her own swing band. Over the next few decades, the Kalakala gained a reputation along Puget Sound ferry routes for a tendency to crash into docks and other boats. The engine is said to have been misaligned, causing a teeth-rattling vibration so that they only filled coffee cups half full in the galley. The ferry was refitted as a seafood processor and brought to Kodiak in 1968. By the 1980’s, the king crab and shrimp fisheries had crashed and its cannery operators went out of business. The ship was abandoned. The Kalakala’s story might have ended there, but a visiting Seattle sculptor saw her and began an epic restoration effort to repair, excavate, and tow the ship back to Puget Sound.

She was met with fanfare when she reached Elliot Bay in 1998, thirty years after leaving. But fundraising efforts failed and the Kalakala was scrapped in Washington in 2015.

~

The 1964 tsunami also inspired Kodiak’s legendary bar, the Beachcomber. Henry “Legs” LeGrue survived the tsunami by running shoeless up the hill as his home and bar, a log cabin, were swept up in the series of waves. Later, as he sat looking at his empty land, he thought, “Wouldn’t a boat look pretty there.” He towed the SS Princess Norah; a 250-foot steamship launched in Scotland in 1929 to Kodiak and on the year’s highest tide used tugboats and bulldozers to prod the ship through a man-made drainage channel and onto a gravel pad next to Potato Patch Lake. LeGrue added exterior stairs and opened The Beachcomber—with a nightclub on the top deck, a dining room on the bottom deck with a wine cellar below, and 50 staterooms for rent. My father in law broke his ankle on one of the ship’s stairways during a brawl. Ask around, and most longtime Kodiak residents can share a Beachcomber story or two, which is all that you’ll find of the ship now, except for the odd porthole or brass fitting in a home or banya around town. It’s these maritime mementos that inspire Terri Springer, a Kodiak setnetter whose fence in Bells Flats merges creativity and practicality in a very Kodiak way.

Terri originally put up the fence to hide her husband’s construction materials and to use up old roofing. Cannery salvaged lightbulb covers led to Terri’s first panel of art.

Now the patchwork of art panels made from miscellaneous found objects—rusted tools, a truck flap, melted glass, spent bullets collected at the shooting range—has become a neighborhood favorite.

Among the 76 panels are mosaic mermaids, jellyfish made from old telephone bells, shoes, self-portraits on driftwood, flowers and pinwheels cut from cans, a salmon made from oil spill pompoms. “It became a challenge to see how many I could do just with things from my house and yard,” says Terri.

In October, the Springers added a giant mermaid reading a book. She perches above an octopus with Keurig tops for suction cups. Her tail is made of old CDs that flash iridescent as you drive by.

The Springer’s fence fits art and history into its functional form, which is what we value in repurposed bunkers or the Star of Kodiak, and why, after nature takes back ships like the Kalakala and Beachcomber, they remain a part of Kodiak’s landscape—in stories and photos and pieces salvaged for the memories they evoke.